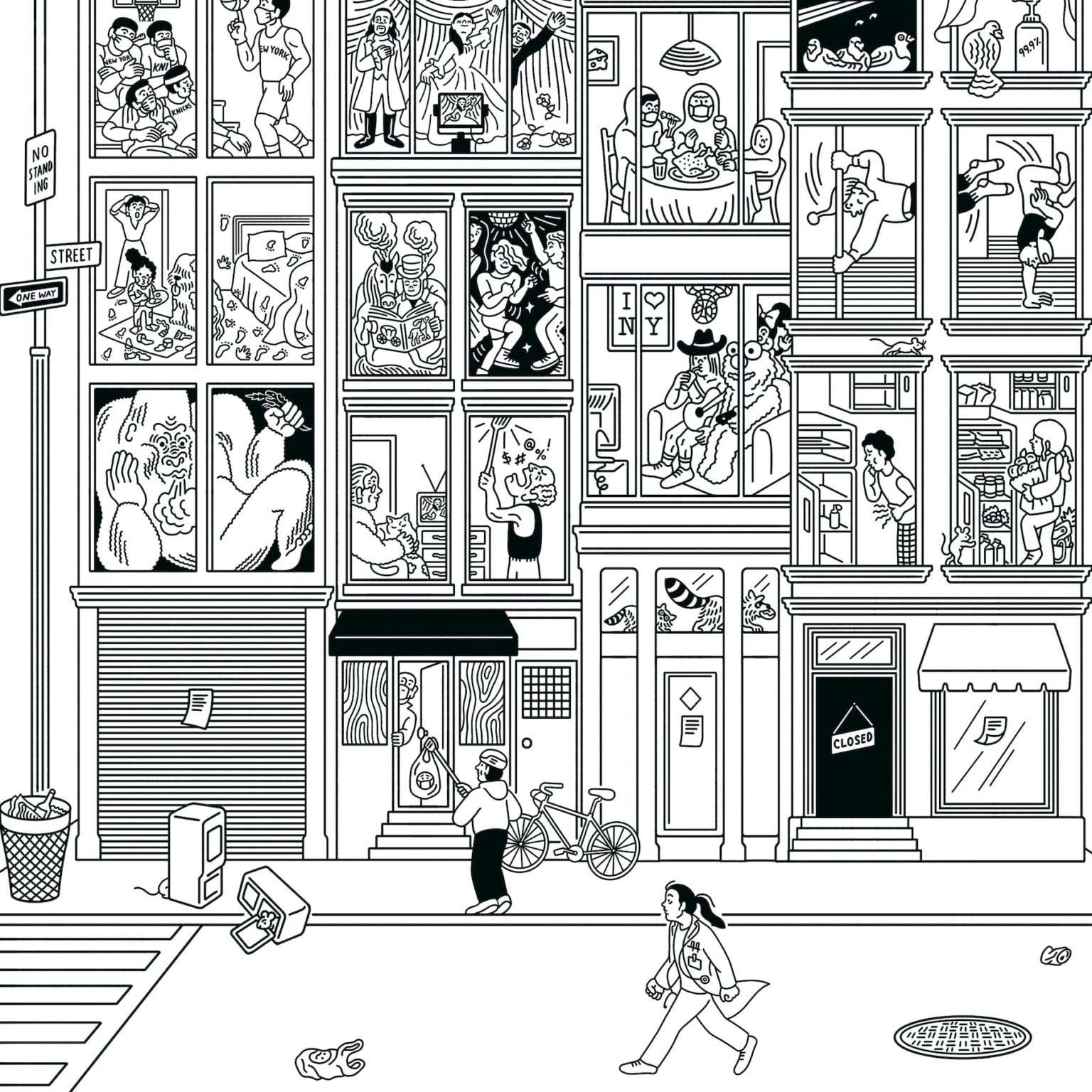

The Art Of "Socializing" During Isolation

Who would have thought our future would rest on our very ability to remain in our homes?

People often think that artists must live troubled lives in order to create truly great art. Whether or not the myth of the “tortured artist” is true, the fact remains that many of the world’s most brilliant artists lived through turbulent periods in history. If you try to imagine the perspective of artists who’ve experienced war, famine, pandemics, and other atrocities, it actually makes a lot of sense. After all, when the world seems to be crumbling around you, why not create something beautiful for future generations?

The close connection between art and larger crises may not be evident at first glance. Artistic periods and movements often transcend individual events and are not always easy to define. That said, some catastrophic health crises had a profound impact on their time, compelling many artists to portray these events with their own unique styles and artistic vision.

The Black Death (Peaked Between 1347-1351)

The Bubonic Plague swept through most of Europe and Asia in the mid-14th Century, killing somewhere between 75 and 200 million people. Despite peaking around 1350, the plague continued to spread rapidly well into the 17th Century. To this day, “the Black Death” remains the single most deadly pandemic in human history.

Somewhat ironically, this plague coincided with the Renaissance, one of the most prolific times in European art history. Apparently death and misery can really get the creative juices flowing! The 14th Century marked the transition from the iconographic early Christian pieces of the Middle Ages to the unique stylization of the new Renaissance. In addition to the Humanistic philosophy taking hold in both politics and art, Renaissance pieces were often characterized by an adherence to linear perspective, something which held little importance in earlier periods.

The Dance of Death (Giacomo Borlone de Buschis, 1485)

Little is known about the life of Giacomo Borlone de Buschis, the painter of this famous fresco at the Oratorio dei Disciplini in Clusone, Italy. Historical documents show that he produced dozens of pieces throughout the 15th Century. The majority of his surviving works are religious in nature, though some (like the one pictured above) take on a more macabre tone.

As The Dance of Death shows, many late Medieval and early Rennaisance artists viewed the plague as death itself. Rather than a disease that could be overcome, the Bubonic Plague was quite literally a death sentence. In this fresco, men dance with skeletons as they approach their demise.

Despite the ostensibly morbid image, The Dance of Death isn’t all bad. This theme helped Rennaisance-era artists display the universality of death. Whether you were a king or a pauper, you had no choice but to participate in the Danse Macabre!

The Triumph of Death (Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1562)

Are you beginning to see a common theme? The Triumph of Death was painted well after the Bubonic Plague had peaked in Europe. However, millions of people still feared the deadly disease. In any case, there’s little room for interpretation in Bruegel’s famous work. The Triumph of Death depicts skeletons marching through the landscape, leaving a path of destruction in their wake.

When examined individually, each section of the painting represents a different facet of the epidemic. Musicians continue playing in the bottom-right, oblivious to their inevitable demise. In the top-left, two skeletons ring a death knell to welcome the end of times. In the background, dead plants and fish reflect the famine that accompanied the Black Death. It’s pretty clear that Pieter Bruegel the Elder had nothing positive to say about the plague!

The Spanish Flu (1918-1920)

Though not quite as devastating as the Black Death, the Spanish Flu was the first major pandemic of the 20th Century. The initial outbreak of influenza occurred in 1918. By the time it subsided two years later, the illness had affected nearly 25% of the world’s population. Ultimately, it killed somewhere between 17 and 50 million people.

The term “Spanish Flu” was coined due to the free reporting in Spain at the time, which made it seem as though the country was impacted more than others. This false assumption allowed people to put blame on the Spanish people for years afterward. Despite the name, the exact origins of the strain are unknown.

Much like the Bubonic Plague, the Spanish Flu had a profound impact on the art of its time. Art of the 1910s and 20s often reflected the sheer chaos of the first World War and the death, disease, and famine that resulted. During this period, Dadaism, Surrealism, and Expressionism arose as three of the most influential art movements.

Dadaism sought to reject capitalism and other traditional structures that led to such terrible death and destruction, while Surrealism rejected the ideals of the Enlightenment, which suppressed the unconscious mind. Finally, Expressionism was a movement born in Germany, emphasizing the portrayal of reality through a highly subjective, emotional lens. All three of these movements helped artists and the population at large cope with a terrifying and uncertain period in human history.

Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu (Edvard Munch, 1919)

Edvard Munch is one of the most celebrated Expressionist painters of the modern era. His most famous work, The Scream, is an iconic image portraying the angst and anxiety of the human condition. Though not one of his most famous pieces, Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu portrays exactly what the title describes — an artist suffering from the Spanish Flu!

In this piece, viewers will note Munch’s gaunt appearance, his body covered in multiple layers of clothing and linens. Throughout his life, Munch showed a keen interest (bordering on obsession) in his own physical and psychological well-being. According to one account, Munch excitedly discussed the painting with his personal physician. During this conversation, he referred to the “odor of death” portrayed in the image. Even though Munch survived the Spanish Flu, his art shows the extent of his paranoia and fear of death.

Sars (2002-2004)

SARS originated in the caves of Wuhan, China, where it transmitted from bats to humans. It would go on to infect more than 8,000 people in dozens of countries, with a fatality rate of approximately 9.6%. The sudden onset and intense media coverage helped heighten measures to combat highly-contagious viruses around the world. Ironically, the panic over SARS ended up saving thousands of lives.

Even though the disease was relatively short-lived, SARS had a profound impact on the people of Southeast Asia. For months, people isolated themselves from the rest of society for fear of catching the deadly disease. This intense fear and isolation impacted the economy, culture, and even art in the region for years afterward.

To this day, you can still see millions of people wearing masks while they go about their day in China, Japan, Thailand, and many other Southeast Asian countries. It has even become a cultural practice associated with the region. However, in many cases, wearing masks just protects people from pollution!

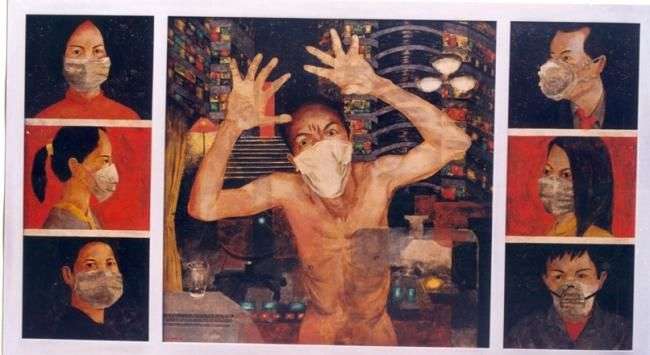

SARS (Tran Tuan Long, 2008)

Tran Tuan Long is a Vietnamese artist who specializes in paintings of Vietnam’s culture from centuries past. After graduating from the University of Art in Hanoi, Tran became a member of the Fine Arts Association of Vietnam. His art has been exhibited in dozens of galleries throughout Southeast East since the early 1990s.

Though the painting above is a departure from Tran’s typical style, it demonstrates the impact that SARS had on an entire region. In this painting, Tran recreates a series of men and women wearing masks. Their expressions range from stoic to fearful. In the center, a naked man in a mask embodies the fear, chaos, and danger of the disease.

Hiv/aids (1980-present)

HIV is thought to have originated in the Democratic Republic of Congo sometime in the 1920s when it moved from chimpanzees to humans. However, it would take almost 60 years before new cases were recorded around the world, setting off what would become one of the worst epidemics of the late 20th Century. There are nearly 40 million people living with HIV or AIDS today, with about 32 million deaths since the epidemic began.

One of the most significant controversies surrounding HIV and AIDS was the initial stigma and slow response to the disease. In the early days of the epidemic, HIV primarily affected gay men, leading to many labeling it a “gay disease,” causing greater discrimination against an already disenfranchised community. Even once it was proven that people of any age, gender, or orientation could catch the disease, the stigma remained, causing untold harm to millions of people.

Apocalypse #1 (Keith Haring, 1988)

Keith Haring began his career creating New York City street art. In the mid-1980s, he gained international attention as one of the leaders of the pop art scene. As an openly gay artist, Haring frequently used his art to speak out on politics and issues like homosexuality, poverty, and HIV/AIDS.

After being diagnosed with HIV, Haring created Apocalypse, a series of paintings that helped him come to terms with his diagnosis. Many of the paintings include sexual, religious, and cultural imagery. The project was also a collaboration between Keith Haring and author William S. Boroughs, whose writings accompany each of the paintings. Though some paintings in the series are difficult to decipher, the phallic imagery in Apocalypse #1 is pretty overt!

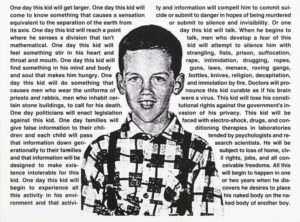

Untitled (David Wojnarowicz, 1990)

David Wojnarowicz was an American painter and political activist who frequently used his art to comment on the experience of gay men in America. His work became even more politically-motivated following his HIV diagnosis in 1987. This discovery also coincided with the AIDS-related death of his longtime mentor and lover, Peter Hujar.

As Wojnarowicz was surrounded by the death and misery of AIDS, he took the opportunity to speak out against those who would use the disease to villanize the gay community. In the untitled painting above — sometimes referred to as (One Day This Kid…) — Wojnarowicz tells the story of a normal American boy. Despite being a loving, caring kid just like anybody else, he must endure hell at the hands of bigots and reactionary authorities.

LGBTQ rights have come a long way since Wojnarowicz first created this painting. However, the effects of HIV/AIDS and bigotry continue to adversely affect millions. Hopefully, future generations will live in a world that is free of HIV/AIDS and LGBTQ discrimination. With the help of artists like Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, and others who document the health crises of their time, we can remember those who have lost their lives to these terrible diseases.