Inside The Factory: The Studio Where Andy Warhol Worked

The Factory may have been the name of Andy Warhol’s studio, but anyone with an interest in 1960s New York will know it was so much more than that. It quickly became the hip place for people from all walks of life — musicians, drag queens, models, socialites, drug addicts, adult film stars, and free-thinkers — to hang out and unleash their creative potential.

As well as assisting Warhol with his own projects, allowing him to rapidly boost the commercial productivity of his art, the studio became famous for its wild parties and influential, experimental artistic expression. As Lou Reed of The Velvet Underground noted: “I was a product of Andy Warhol’s Factory. All I did was sit there and observe these incredibly talented and creative people who were continually making art, and it was impossible not to be affected by that.”

Here we uncover the legendary history of Andy Warhol’s Factory.

How Did The Factory Get Its Name?

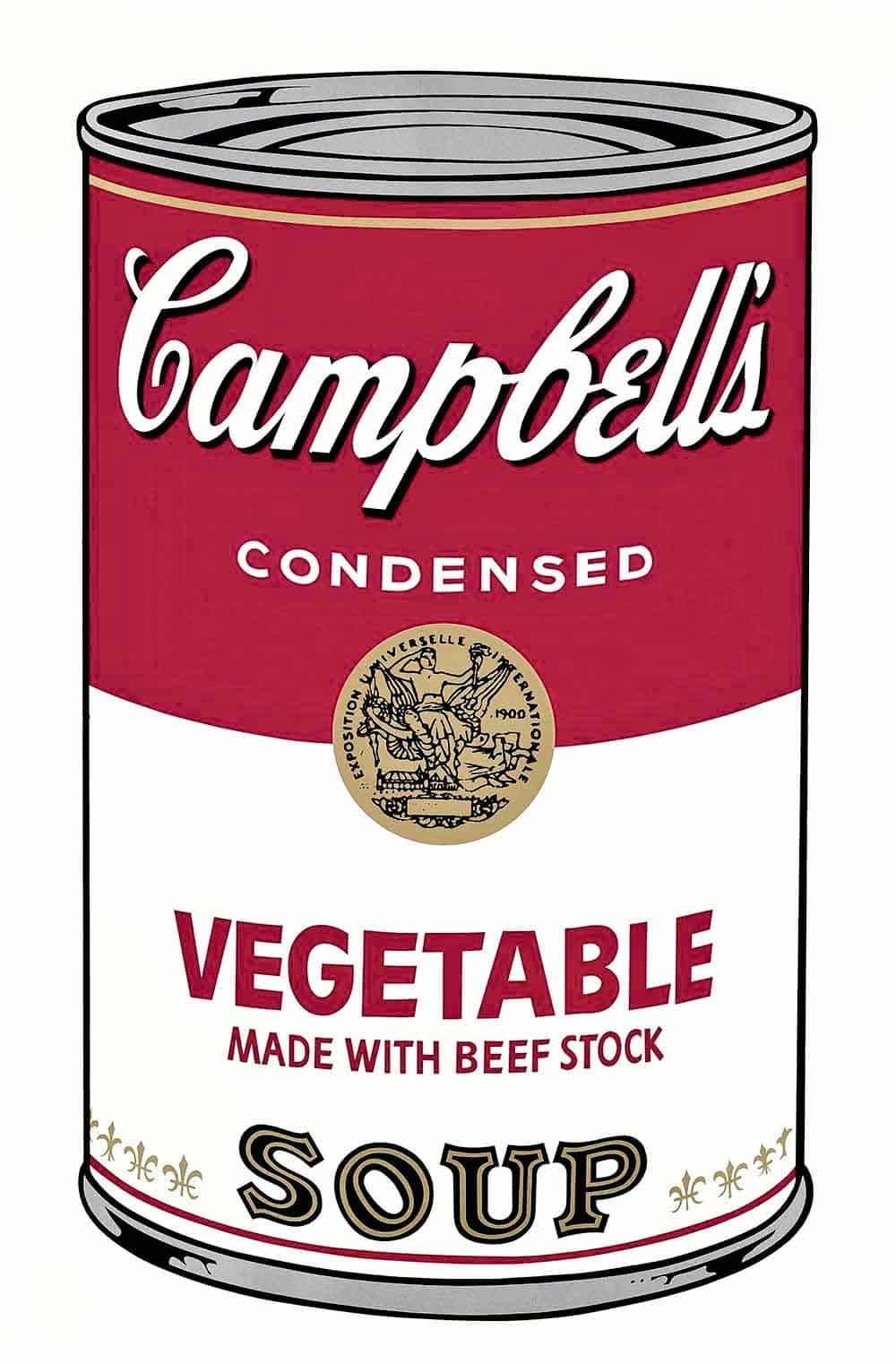

With their focus on mass production and consumerism, factories aren’t things one would typically associate with art and creativity. However, considering the mechanical nature of Andy Warhol’s pop art, this was a fitting name for his place of work.

In opposition to the prevailing elitist connotations surrounding art, Warhol pioneered a more commercial production approach. He had no interest in creating pieces just for the wealthy, and instead targeted the masses by placing pop culture figures at the heart of his work, especially products and celebrities. This subject matter appealed to wider society, and enabled him to target the masses. In theory, just as anyone could own any factory-made item, anybody could own a Warhol.

The Factory’s name is even more fitting given the silk-screening process by which Warhol actually produced his work. Rather than painting every piece by hand, he would simply transfer his stencilled designs, allowing him to reproduce a work multiple times and churn out prints at great speed. And prints weren’t the only things created in the studio. As Velvet Underground co-founder John Cale told The Guardian in 2002: “It wasn’t called the Factory for nothing. It was where the assembly line for the silkscreens happened. While one person was making a silkscreen, somebody else would be filming a screen test. Every day something new.”

Where Was The Factory?

The Factory had three different New York City locations between 1963 and 1984:

The fifth floor at 231 East 47th Street in Midtown Manhattan (1963-1967)

The first Factory is by far the most famous. It was also known as the Silver Factory, after photographer Billy Name (who documented all the goings-on there) sprayed the studio silver and decorated it with aluminium foil. As well as a place of work, the Factory became a social hub for other creatives, renowned for its hedonistic parties.

The sixth floor of the Decker Building at 33 Union Square West (1968-1973)

Warhol was forced to relocate due to plans to redevelop the building into apartments. His new premises at the Decker Building were far more business-oriented, rather than being home to a social scene. This may well have come as the result of a shocking attempt made on his life in 1968, when he was shot by writer Valerie Solanas. The artist never fully recovered from his injuries, and had to wear a surgical corset for the rest of his life. Security was subsequently tightened, and many considered this to be the end of the “Factory sixties”.

860 Broadway at the north end of Union Square (1974-1984)

This space was much larger than previous Factory buildings, but very little filming took place here. In 1984, the concept of Factory ended, with Warhol instead buying the Edison Building on East 33rd Street. This was where he based his studio and office, as well as Interview, the magazine he founded in 1969.

What Works Came Out Of The Factory?

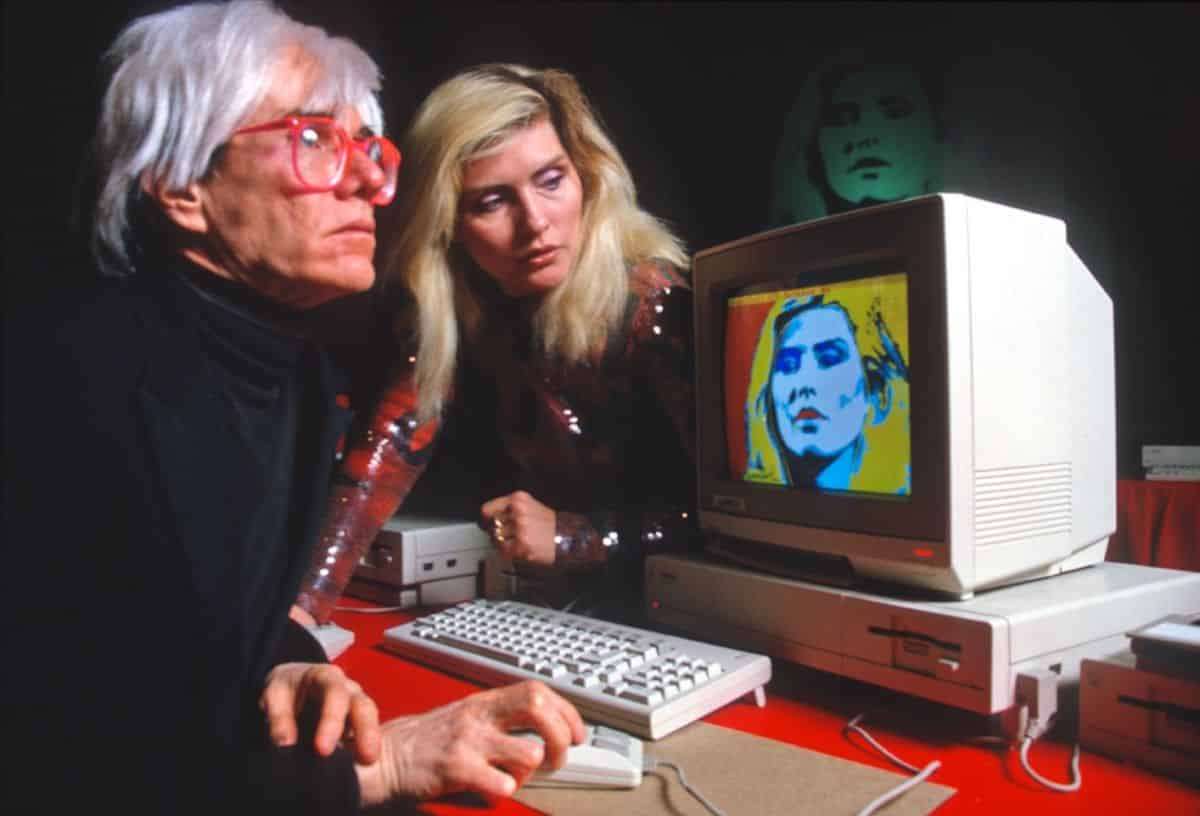

Warhol is probably most famous for his silkscreen paintings like Campbell's Soup Cans and his Marilyn Diptych, while notable photographs from the Factory show the artist alongside pieces including Flowers and Cow. However, the collaborative essence of the environment also gave him the perfect opportunity to get involved in a variety of other creative endeavors.

FILMS

Warhol produced hundreds of films at the Factory. These experimental works often consisted of unstructured, improvised scenes, and starred many of the ‘Warhol superstars’, including his most infamous muse, model Edie Sedgwick.

Warhol withdrew the majority of his films from circulation in 1970. However, in 2014 it was announced that New York’s Museum of Modern Art planned to digitize and screen 500 of the films he created between 1963 and 1972. “I think the art world in particular, and hopefully the culture as a whole, will come to feel the way we do,” Patrick Moore, a curator of the project, said. “The films are every bit as significant and revolutionary as Warhol’s paintings.”

FEATURES

Blue Movie (1969), one of his most famous films, became the first adult erotic picture including explicit sex to get a wide theatrical release in America. Other notable features are Vinyl (1965), an adaptation of the novel A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess, and Sleep (1964) which depicts poet John Girono sleeping for almost five and a half hours.

Chelsea Girls (1966) was Warhol’s most critically and commercially successful film, following the lives of women that lived at New York’s Chelsea Hotel.

SCREEN TESTS

As well as his features, Warhol also became famous for his non-traditional ‘screen tests’ he took of his famous friends. These were films in their own right, rather than auditions to test their suitability in front of the camera. Each was only a few minutes long and totally silent, with the subject instructed to stay as still as possible in order to create a living portrait. That said, Warhol’s stars would often deviate from this format in later films and move freely, showcasing their personalities in spite of the restrictions. Some of his most famous subjects include Bob Dylan, Salvador Dalí and Marcel Duchamp.

MUSIC

The Factory was frequently visited by many iconic musicians. Warhol soon became manager and mentor to the Velvet Underground, designing the legendary cover of their debut album

The Velvet Underground & Nico, complete with a peelable banana. He also financed the recording sessions, and persuaded the band to feature German singer Nico, another Warhol superstar.

After leaving the Velvet Underground, frontman Lou Reed released the single ‘Walk on the Wild Side’, one of his most famous songs. Each verse of the track refers to one of the regular Warhol superstars at the Factory — Holly Woodlawn, Candy Darling, Joe Dallesandro, Jackie Curtis and Joe Campbell. The lyrics were groundbreaking for the time, owing to their risqué nature, referencing the real-life exploits of the superstars with allusions to prostitution, transgender people, and oral sex.

Another musical face at the Factory was Mick Jagger, for whom Warhol designed the suggestive cover of the Rolling Stones’ 1971 album

Sticky Fingers. Featuring a close-up of a male crotch in tight jeans, the album sleeve could be literally unzipped to reveal the underwear beneath.

MULTIMEDIA

Warhol also teamed up with The Velvet Underground, Nico and other Factory denizens to create The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, a series of multimedia concert events held between 1966-67. The group would perform alongside screenings of Warhol’s films, dancing, live S&M enactments, and more. Many Factory regulars would take part, particularly Mary Woronov and Gerard Malanga. These theatrical ‘happenings’ would be staged at parties and in public venues in New York and various other cities in the US and Canada. Although popular with the artier parts of the sixties counterculture, other “straighter” celebrities were less keen on the events, with Cher allegedly once overheard to quip that the Exploding Plastic Inevitable “will replace nothing, except maybe suicide.”

The Factory’s Legacy

Decades after Andy Warhol’s Factory was founded, people remain fascinated by the events and work that took place there. The studio continues to be a symbol of transgressive artistic expression and 1960s cool, and has been widely celebrated in films, books, music, and other visual arts.

As well as enduring from a pop cultural perspective, Warhol’s way of working at the Factory has also inspired a number of artists to follow the artist’s collaborative approach. “One of Andy’s great innovations was realising that the idea of the artist alone in his studio was not a particularly modern one, and that an artist could have a team,” Glenn O’Brien, a journalist who worked with Warhol on Interview told The Guardian in 2012. “Today you have artists like Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst who employ hundreds of people — it’s a very understandable model for artists.”

Undoubtedly the Factory gave birth to an unprecedented cultural revolution, and there’s yet to be another artist’s studio that so perfectly encapsulates a particular time, place and artistic temperament.