Behind The Lens Of Vogue: How Fashion Photographer Helmut Newton Defined The Magazine’s Aesthetic

To say Helmut Newton was expecting the worst when he arrived at British Vogue in the late 1950s would be an understatement. “The Vogue studios in Golden Square were depressing and dusty, with terrible old wooden floors,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I was told that under the grassy square were the bodies of people who had died during the black plague. It was indicative of my whole feeling for the place.”

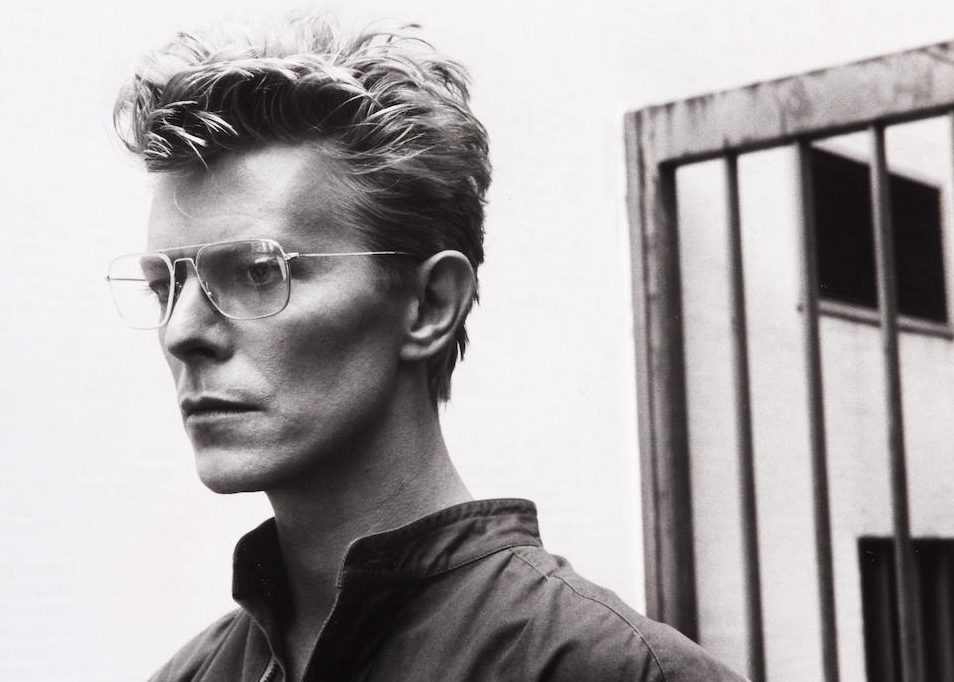

Although he only saw out 11 months of his year-long contract, he eventually became a regular contributor, going on to work with the French, American and Australian strands of the fashion bible, and establishing himself as one of the most prolific photographers in the world. Also known as ‘the King of Kink’, Newton brought irresistible glamour and sex appeal to the art of fashion photography, printing provocative shots of powerful women on Vogue’s pages. In addition, he shot A-listers including Jerry Hall and David Bowie for the magazine.

Here we delve into the essence of Newton’s work, and how he defined the Vogue aesthetic in the decades he worked with the publication.

Sex Sells: Fashion & Erotica

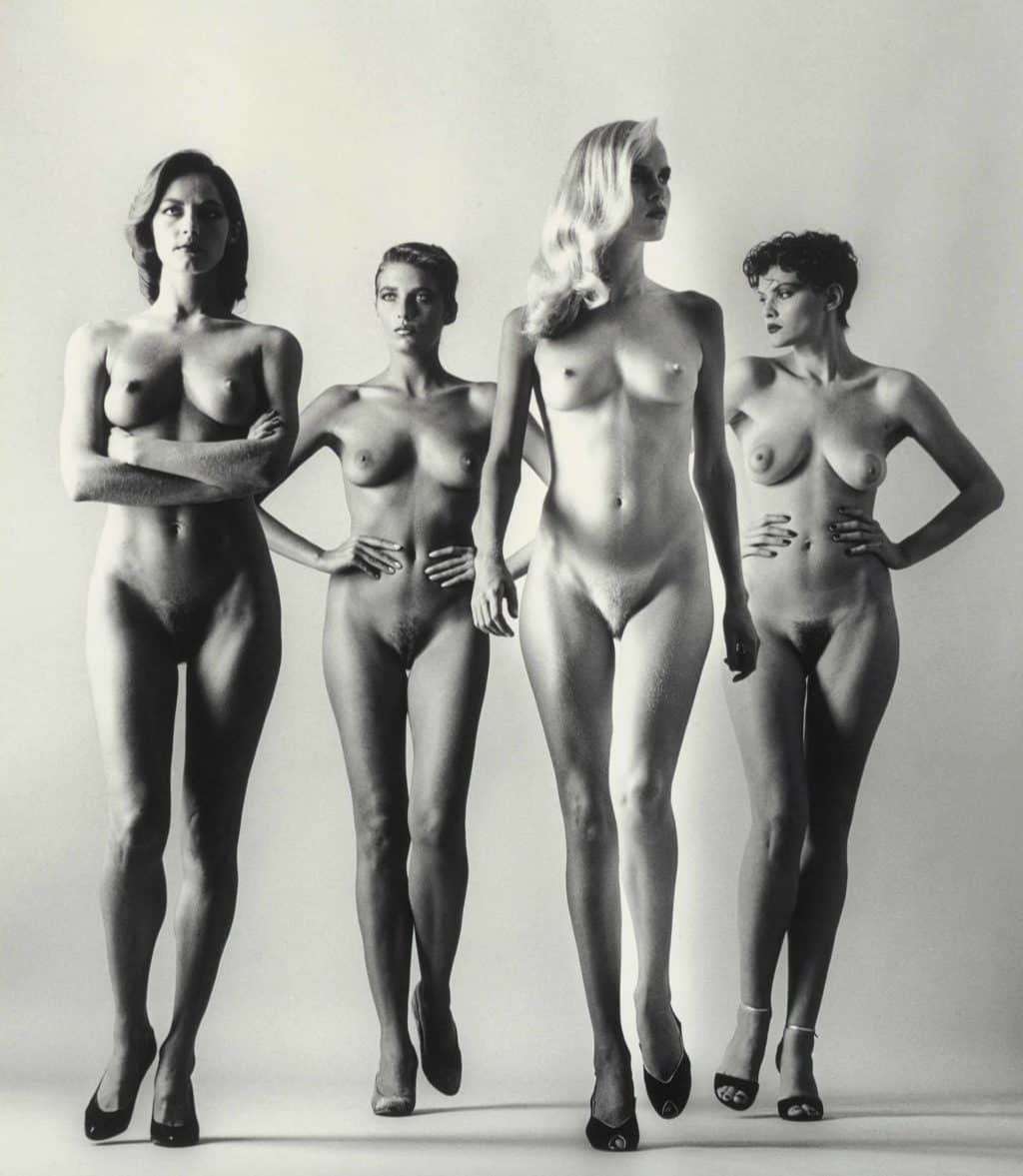

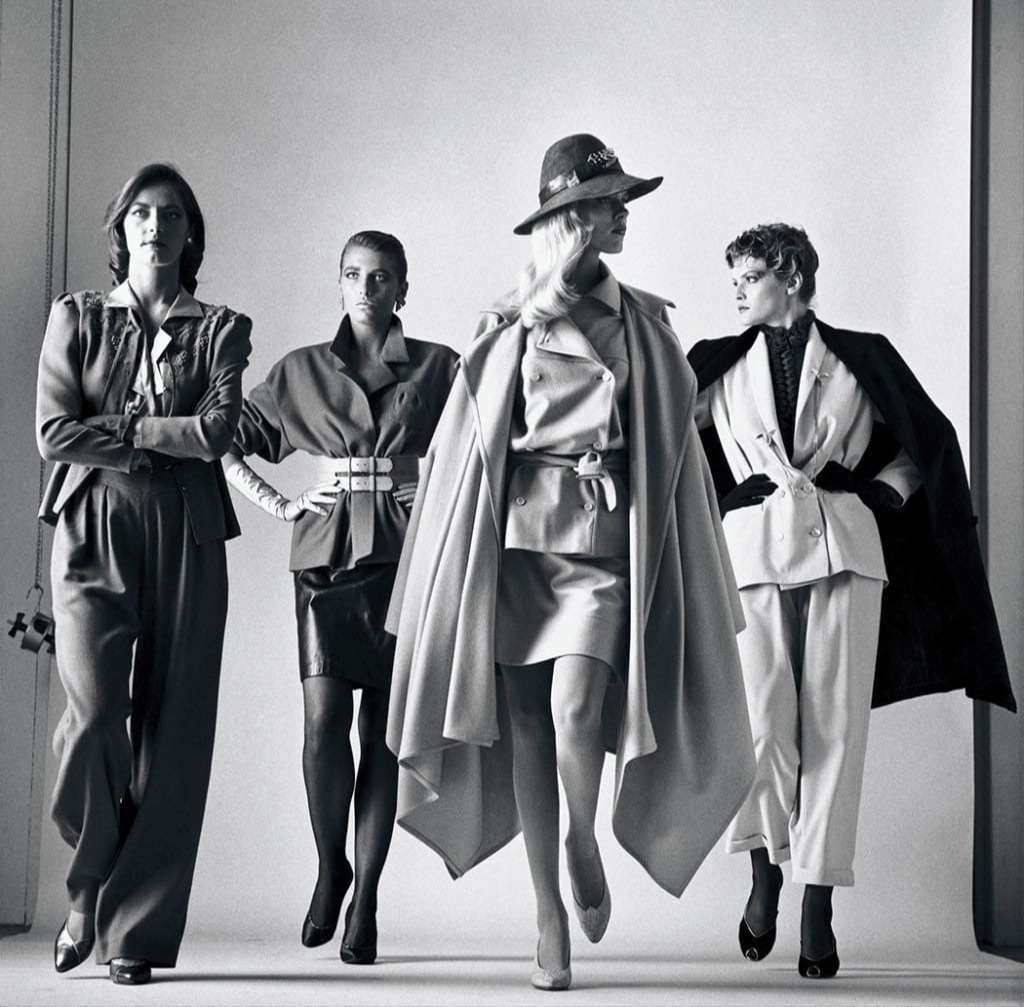

Strong, sexy women were Newton’s subjects of choice, posed in fetishistic fantasy scenarios which were totally at odds with the prevailing conservative depictions of femininity. His risqué black-and-white photographs were unashamedly provocative, presenting erotically charged images of women exerting power through assertive sensuality. Newton’s work was exciting and, unlike conventional fashion photography of the time, certainly left a lasting impression on Vogue readers.

It perhaps seemed counterintuitive to show his subjects in a state of undress when the magazine’s purpose was to present clothing in an appealing way. Newton hugely disrupted the function of fashion photography by demonstrating just how strong and confident women could be without clothes. Take his famous pair of images Sie Kommen (Nude) and Sie Kommen (Dressed), printed in Vogue Paris in 1981. While four women look spectacular wearing beautiful haute couture in one photo, the same quartet is just as powerful wearing nothing at all.

Interestingly, doing this also allowed him to tap into something that fashion photographers still strive for today, which is to say that a Newton woman definitely didn’t lead an ordinary life. As Robin Muir comments in the aforementioned Vogue article: “the trials of quotidian life did not exist; she would never run for a taxi, shop for groceries or turn up at the school gates […] she inhabited ‘a Nietzschean Disneyworld of pretend power games and kinky joy rides’”. By flaunting these unobtainable images of glamour, not only did Newton sell sex, but he also sold a fantasy that was far more powerful than any item of clothing could ever be.

Subverting Gender & Power

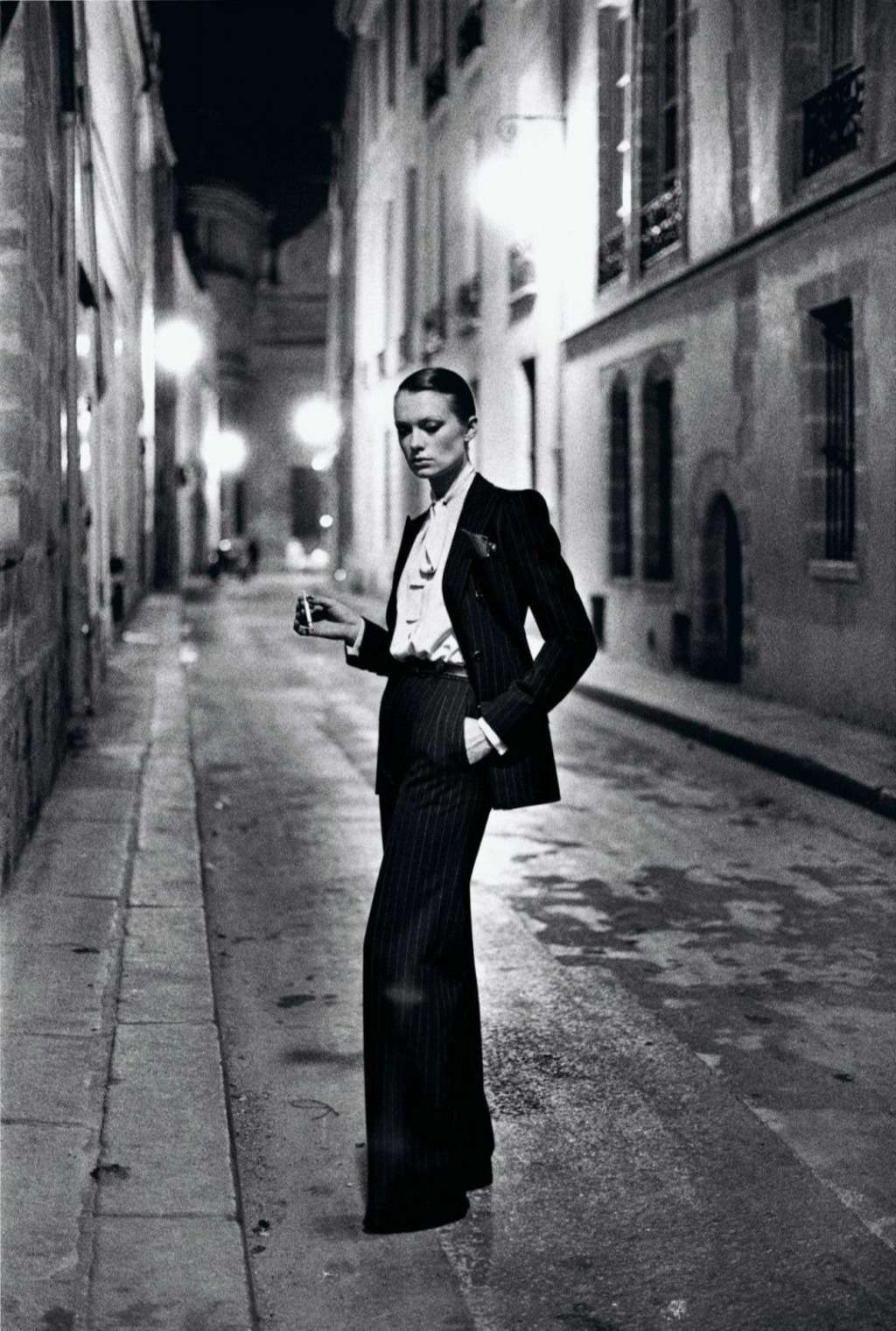

The power play at the heart of Newton’s imagery successfully pushed the boundaries with regard to gender and identity. The women are dominant and certainly aren’t to be messed with. As British fashion designer Lee Alexander McQueen said during a 2001 interview with the photographer: “Newton’s women look like if you tried to touch them, they’d bite your arm off. And maybe not just your arm.” Meanwhile, the men merely serve as their accessories — a point emphasized by recurrent phallic props like cigarettes.

Newton’s subversion of gender norms is perhaps best illustrated in Rue Aubriot, published in Vogue Paris in 1975. The model is fully dressed in an Yves Saint Laurent ‘Le Smoking’ tuxedo at a time when women were very rarely seen in trouser suits. Other images from the series — Nude Rue Aubriot and Kissing Rue Aubriot — also challenge traditional ideas of femininity by juxtaposing this androgynous woman with a nude woman (aside from a veil and some high heels) who appears to be just as powerful. The contrast highlights the fluidity of gender and sexuality by indicating that there is no one version of ‘female’.

Courting Controversy

Newton’s refusal to stick to tradition is what ultimately made him an icon, but of course, this also meant he had some very vocal critics. Many readers went so far as to cancel their subscriptions to American Vogue after a raunchy set of Newton photos called ‘The Story of Ohhhh’ — named for an erotic French novel from the fifties — were published in 1975. However, Newton wasn’t fazed, simply saying: “The fact that her [model Lisa Taylor] legs were open didn’t seem very important to me. She had a big skirt on…” There were also cancellations in 1967 over photos of Twiggy throwing a cat in the air.

And although Newton insisted his work was empowering women, not everybody agreed. In the film Helmut Newton: The Bad and the Beautiful, we see footage from a French chat show where writer Susan Sontag says “a lot of misogynous men” claim to love women, as Newton does. In the post #MeToo era, plenty of people may see Newton’s work as a symbol of the patriarchy, with his female subjects objectified through a male camera lens.

Yet it’s important to remember that even though these images were the imaginings of a man, they were created for women to enjoy, plus many of Newton’s stars were completely on board. “He was a little bit pervert (sic), but so am I!” singer Grace Jones says in the film, while model Sylvia Gobbel claims: “Helmut Newton’s photos made me stronger. I controlled the situation, I wasn’t the deer, I was equal to the hunter, I could decide what I wanted to do.”

Any art that seeks to disrupt the status quo is sure to be divisive, and Newton’s images will always be subject to interpretation. However, in spite of his apprehensions at the start of his Vogue career, he redefined what fashion photography could achieve, leaving a legacy that continues to influence the medium to this day.